A multifaceted intellectual and political activist, Jose Rizal was best known for his advocacy for reforms in the Philippines under Spanish colonizers and soul-stirring writings that inspired the Philippine revolution and eventually led to his execution.

Aside from being the epitome of greatness and nationalism, he was also famous for having a long list of old flames. There are nine on record but not all of those relationships were serious.

But amidst the dalliances, Rizal championed women empowerment. This was evident in his essay, “To the Young Women of Malolos”, which emphasized that women must have the same opportunities given to men in terms of education.

As we commemorate today, June 19, Rizal’s 162nd birth anniversary, let’s take a glimpse of his romantic interests.

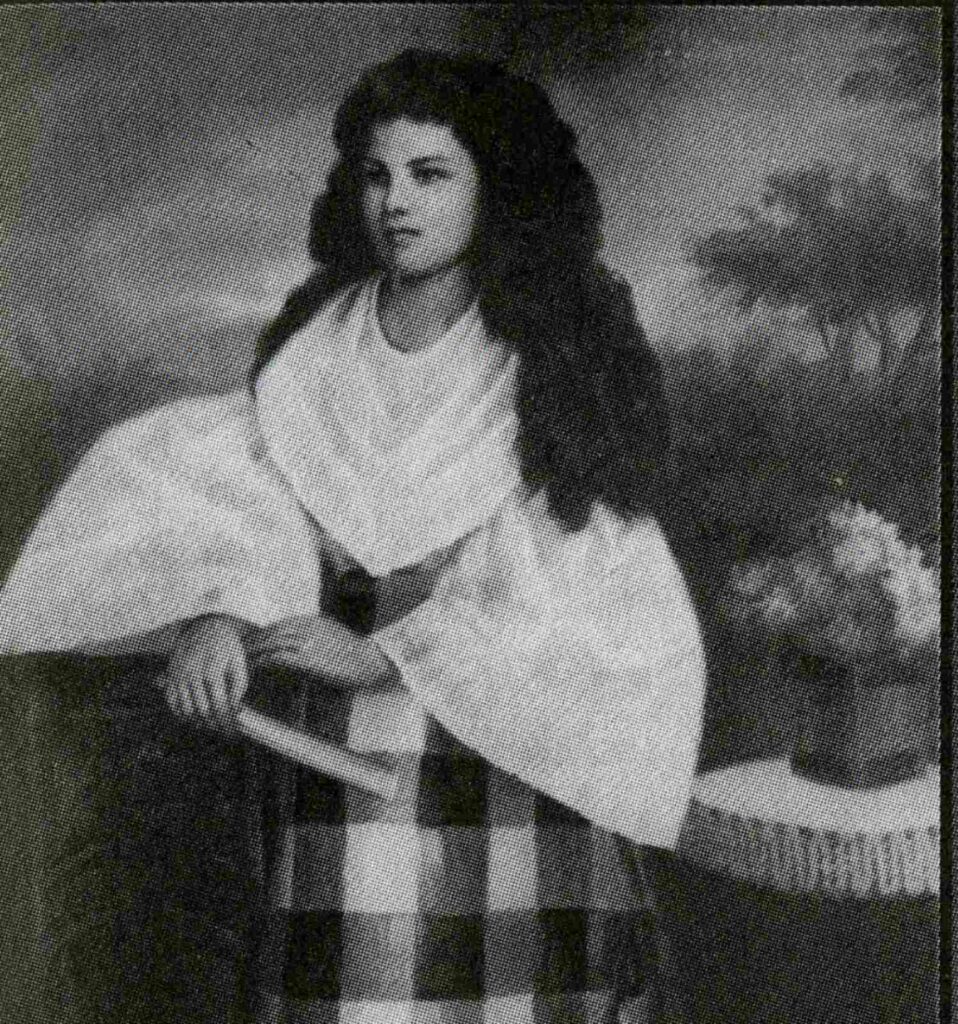

Segunda Katigbak

First love never dies, they say – unless your first love is already engaged to be married. Then you have to let it go. Such was the case of Rizal and Segunda Katigbak.

Katigbak was Rizal’s “puppy love”. Coming from a wealthy clan in Lipa, Batangas, she was a close friend of Rizal’s sister, Olympia Mercado.

Katigbak was just 14 years old when she met Rizal who was then 16. They didn’t end up together. Our hero was not able to confess his true feelings and she was promised to Manuel Luz y Metra, a member of a wealthy family in Lipa. Katigbak and Metra had 12 children but only nine survived.

Rizal wrote about the incident years later, “Ended, at an early house, my first love! My virgin heart will always mourn the reckless step it took on the flower-decked abyss. My illusions will return, yes, but indifferent, uncertain, ready for the first betrayal on the path of love.”

Our hugot-induced breakup movies would be put to shame.

Leonor Valenzuela

Leonor “Orang” Valenzuela met Rizal when he was a sophomore medical student at the University of Santo Tomas, during which time he also lived at Doña Concha Leyva’s boarding house in Intramuros, Manila. Valenzuela, who was then 14 years old, was his neighbor.

Rizal pursued her by sending love letters with invisible ink that one can only read when it is heated over a candle or lamp. The ink is a mixture of substances that he learned from his chemistry class. (How did we get from this complicated manner of courtship to pressing that heart icon on Instagram?)

Rumor has it that Rizal used the invisible ink because he was courting Leonor Rivera at the time. (Still, the effort that went with it is laudable.) When Rizal left for Spain in 1882, he did say goodbye to Valenzuela, but kept in touch with the help of Rizal’s friend, Jose “Chenggoy” Cecilio, the ultimate teaser – and maybe wingman? – who was amused with the “rivalry” of the namesakes.

While he was pursuing the two Leonors, Rizal was in Europe taking medical courses at Universidad Central de Madrid and painting at Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Calle Alcala. (His juggling act is admirable.)

Leonor Rivera

Leanor Rivera and Rizal lived the tragedies of Shakespeare’s poems.

They met when he was 18 and she was 13, at the boarding house of Rizal’s uncle in Intramuros, Manila. Rivera was Rizal’s second cousin.

It was a perfect love story in the beginning: he, the intelligent charmer, and she, the beautiful student who had a beautiful singing voice and was a talented piano player. Soon, they fell in love. But as tragic love stories go, they were besieged by obstacles. Rivera’s parents vehemently disapproved of their relationship as they were wary of Rizal being a “filibuster”. In his letters, Rizal called Rivera “Taimis” to hide her identity.

Before leaving for Europe in 1882, Rizal said that he had found the woman he wanted to marry. But even his brother, Paciano Rizal, disagreed with the idea, saying that it would be unfair to Rivera if he were to leave her behind after getting married.

Although they did not get married, they continued sending each other love letters, a lot of which were kept hidden by Rivera’s mother. In 1890, Rivera wrote a letter to Rizal saying that she was already engaged to Henry Kipping, a British engineer who helped build the Manila-Dagupan Railway system in the same year.

Some accounts claim that Rivera burned Rizal’s letters to her, but she kept the ashes in the hem of her wedding gown. When Rivera died during her second childbirth, documents showed that Rizal did not speak for days.

Rizal immortalized Rivera through Maria Clara’s character in “Noli Me Tangere”. Rivera was Rizal’s “the one that got away”.

Consuelo Ortiga y Rey

In Madrid, Rizal, age 23, courted Consuelo Ortiga, age 18, the daughter of Pablo Ortiga y Rey, who was once mayor of Manila and who owned the apartment where the Circulo Hispano Filipino met regularly. All the young Filipino expatriates courted Consuelo, and she in turn encouraged everyone including Rizal, Eduardo Lete, the Paterno brothers (Pedro, Antonino, Maximiano), Julio Llorente, Evaristo Esguerra, Fernando Canon and others.

Rizal gave Rey gifts: sinamay cloth, embroidered piña handkerchiefs, slippers – all ordered through his sisters in Calamba. Rey accepted all the swains’ gifts but played Lete against Rizal. She finally rejected Rizal’s attention in favor of Lete, a Filipino-Spanish mestizo from Leyte.

Although most accounts say the dalliance didn’t turn serious, Rizal wrote a poem for her entitled “A la Señorita C.O. y R.” These days, when you write a poem for someone, that’s like a marriage proposal. Or maybe, their case was a rebound fling.

Seiko Usui

In many of his diary entries, Rizal wrote about how he was charmed by Japan’s beauty, cleanliness and peace and order. But if there was one thing that almost kept him in the country where cherry blossoms bloom most beautifully, it was a woman named Seiko Usui, affectionately called O-Sei-San.

O-Sei-San and Rizal met when the latter was still working at the Spanish legislation in Tokyo. Their friendship blossomed after Rizal asked a gardener to introduce him to O-Sei-San who was surprisingly fluent in English and French, two languages that Rizal knew how to speak.

In many accounts, it was written that Rizal almost moved to Japan permanently to spend his remaining days with O-Sei-San; however, his patriotic responsibilities kept him from doing this. He moved to San Francisco and never met the Japanese woman again. Their affair lasted for around two months. It’s shorter than an average season of a Netflix series, but you know Rizal and his intensity.

Like Valenzuela, O-Sei-San went on with her life and later married Alfred Charlton, a British chemistry teacher in Tokyo.

Gertrude Beckett

In the same year, he began and ended his relations with O-Sei-San, Rizal, who was then 27, went to London and met a woman named Gertrude Beckett, the eldest daughter of his landlord, Charles Beckett.

Beckett showered Rizal with all the love and attention of a girl who is hopelessly in love. She even assisted Rizal as he finished some of his famous sculptures, Prometheus Bound, which depicted the Greek legend Prometheus who brought fire to man; and The Triumph of Death over Life, a clay figure of a young, nude woman bearing a torch; and The Triumph of Science over Death.

Despite having pet names for each other (Rizal calls Beckett “Gettie” while Beckett calls Rizal “Pettie”) the feelings Beckett had for Rizal were not reciprocated.

In 1889, Rizal left London and left her a composite carving of the heads of the Beckett sisters. Marcelo del Pilar, Rizal’s friend, said Rizal left London to move away from Beckett, whose idea of their relationship was more than what it really was – the most tormenting kind: an unrequited love. Basically, Beckett was friend-zoned by Rizal.

Suzanne Jacoby

When he arrived in Belgium in 1890, he lived at a boarding house that was run by two sisters whose last name was Jacoby. The sisters had a niece named Suzanne. In his six-month stay in Brussels, Rizal and Jacoby had a transitory romance.

In August 1890, Rizal left Belgium but he left the young Jacoby a box of chocolates, which the latter did not eat nor touch. Many historians believed that the affair was one-sided, as evident in the letters sent by Jacoby to Rizal.

Rizal may have replied once. In 1891, Rizal went back to Belgium – not for Jacoby – but to finish writing “El Filibusterismo”. He stayed for a few months, left and never returned. Maybe Jacoby got the point after that.

Nellie Boustead

Remember when Antonio Luna and Rizal almost got into a duel because of a girl? The girl in the middle of that madness was Nellie Boustead. Rizal and Boustead met in Biarritz, where the latter’s wealthy family hosted his stay at their residence on the French Riviera. Before Biarritz, Rizal already made friends with the Boustead family a few years back, and even played fencing with Nellie and her sister.

During his stay at the beautiful Biarritz vacation home, Rizal learned of Rivera’s engagement and thought of pursuing a romantic relationship with Boustead, who was classy, educated, cheerful, and athletic. After strengthening their relationship, Rizal wrote letters to his friends, telling them about his intention to marry her. They were all supportive, including Antonio Luna, who at that time, also had feelings for Boustead.

Although they seemed like the ideal couple, marriage for Rizal was still not meant to be. Boustead demanded Rizal to convert to the Protestant faith but he refused. Her mother also frowned upon Rizal’s background, saying that she did not like a doctor without enough paying clientele. They ended up being friends after all the drama.

It was more a Rizal licking-of-wounds love after having been spurned by Rivera. Boustead and Rizal were the perfect example of pinagtagpo pero ‘di tinadhana.

Josephine Bracken

Josephine Bracken was the daughter of Irish parents James Bracken and Elizabeth MacBride. During Rizal’s exile in Dapitan, he met the 18-year-old Bracken whom he described as “slender with blue eyes, dressed in elegant simplicity with an atmosphere of light gaiety.” The relationship between the two blossomed quickly but one of Rizal’s sisters suspected that Bracken was a spy of the Spaniards. Nevertheless, Rizal loved her and affectionately called her Josefina.

As a mason, Rizal could not wed Bracken; however, the latter bore him a stillborn son who was named Francisco in honor of Rizal’s late father. Bracken last met Rizal in the latter’s cell in Fort Santiago on Dec. 30, 1896.

Bracken is the foreigner alluded by Rizal in his poem “Mi Ultimo Adios” (My Last Farewell), where he wrote: “Farewell my sweet foreigner, my darling, my delight.” She was Rizal’s great love.

Unknown flings

The aforementioned nine women appear in all biographies of Rizal. However, Rizal’s writings over the years indicate references to women whose names are lost in history, according to historian Ambeth Ocampo.

In his column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Ocampo mentioned a woman Rizal encountered while she was chasing butterflies who’s only known as “M” or “Minang”, a prostitute in Vienna who has become the missing link in the urban legend that makes Rizal the father of Adolf Hitler.

Then there is the woman hidden under the letter “L” whom he visited after jilting his first love Katigbak: “I spent the two nights that followed this day in visiting, together with L., a young woman who lived toward the east in a little house at the right. She was a bachelor girl older than we were. She was fair and seductive and with attractive eyes. She, or we, talked about love but my heart and my thought followed (Segunda) Katigbak. Through the night to her town … my father, who had learned about our visits, prohibited us from continuing them, perhaps because the name of the Oriental maiden did not figure in his calculations. I did not visit her again.”

Then there are other names provided by Rizal himself in a diary entry in May 1882: “Leonores, Dolores, Ursulas, Felipas, Vicentas, Margaritas, and others: Other loves will hold your attention and soon you will forget the traveler. I’ll return, but I’ll find myself alone, because those who used to smile at me will save their charms for others more fortunate. And in the meantime I fly after my vain idea, a false illusion perhaps. May I find my family intact and afterward die of happiness!”

There were also the codes in the letters of Cecilio to Rizal. For example, in a letter of August 1882:

“We played tresiete (T…, O…, Galicano, and I), but afterwards O… spread out her cards and asked me to bet on one of them. Without hesitation I bet you on a horse against one five and I won. Then I told her that it was a clear proof that what I told her about her love affairs were true. I don’t know if she understood that you were the proxy of S … but I informed her that he was present and she knows too well who he is.

“T…, your intimate friend, how she remembers the things that you used to do when she was single. She requests me to give you a pinch of her F…, born after your departure from this capital city. They asked me how long were you going to stay there and I answered them that at least 10 years and when you returned you could make love to F… Then Orang, Candeng, Chengoy, and Titay, who were present, answered that you would kiss their hands … I rejoined that there was no other remedy, but Mariano, brother of Mentang, split the subject in the middle saying that it could not be so for the reason that you ought to have two objects. Here Troy burned. All of them, including Capitana Sanday, send you their most affectionate regards and Orang wishes you to find there a good-looking girl.”

In spite of his great achievements, Rizal was just as human as the rest of us and his love life is proof of that. Maybe he was not meant for a long-term commitment like marriage – with all his travels and freedom-fighting obligations. And maybe he just always needed a companion. He gets a pass – even when he was a master in ghosting.