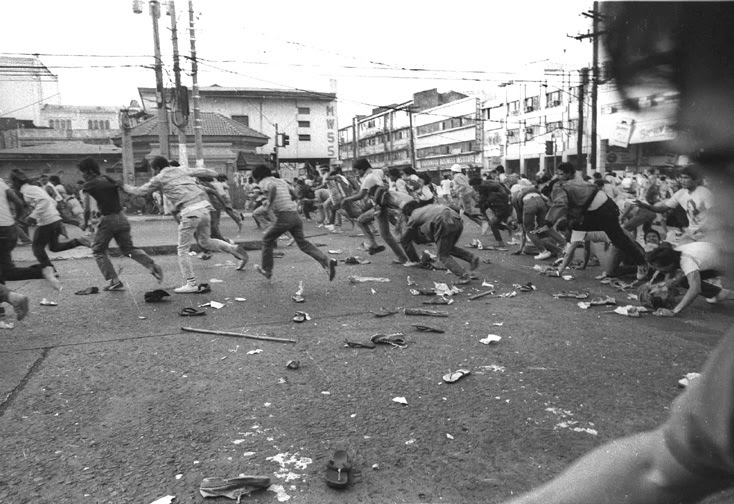

“DIYOS ko, ‘wag Mo ‘kong pabayaan. Maglilingkod pa ‘ko sa sambayanan!” (My God, don’t forsake me. I will still be serving the people!)

Not even for a nanosecond did the gunfire stop. As gunfire roared—while faced down on the pavement by the wall of Corona Book Supply—I kept hearing a male voice reverberating, giving me the impression that it was coming from someone who had been aimlessly, mindlessly walking around. Amid the gunfire? I thought then that it must have been a “doomsday” fanatic whom I occasionally saw in various parts of Metro Manila: wearing long white gowns scribbled with strange handwritings, sporting long disheveled hair, looking up the sky, as if looking for some faraway sign, with eyebrows furrowed. I thought it was someone like him.

Then I understood his words. “Diyos ko, ‘wag Mo ‘kong pabayaan. Maglilingkod pa ‘ko sa sambayanan!” (My God, don’t forsake me. I will still be serving the people!) He kept imploring, repeating those words. In anguish. As he uttered “Maglilingkod pa ‘ko sa sambayanan!” (I will still be serving the people!), there was stubbornness, persistence—unrelenting, even defiant—conviction. Service to the people was his only reason for wanting to live longer. The tone of his voice conveyed that he knew that nobody at that precise moment can help him. His utterance became slower and slower; his voice, fainter and fainter.

I was surprised to realize that the voice belonged to the same bloodied man whom I saw earlier near the gutter. His was the voice that kept reverberating earlier as if walking around aimlessly as I was faced down on the ground by the wall of Corona Book Supply. I glanced at him and saw one of his raised hands weakening, slowly falling down to the ground.

Mystical moment

From the edge of the wall, Mat and I got back to the gutter. We were about two meters away from the same bloodied man. He was still lying on his back. His other arm was still raised, gesturing for help.

Mat told him: “Pare, steady ka lang diyan.” (Bro, just lie in there.)

Mat’s words to the man were soothing. Those were suffused with the energy of pagdamay and pagmamalasakit (core Filipino cultural ethos that embody and manifest the synthesis of lovingkindness, compassion, empathy, and concern for others in an active way and by means of direct, concrete action). I felt grateful and looked up to Mat with gratitude and total respect. To me, Mat’s words made an enormous difference to the person.

As Mat uttered those words, I saw the man’s weakening. His arm slowly fell to the road pavement. Slowly, his head turned to his side facing us. We moved back again towards the wall of Corona Book Supply. The man’s silence crept up on me. Amid the chaos, I was mesmerized. I saw a mist quickly rise up and briefly turn into a cloud on top of him. Although I was aware that the mist did not originate from his environs, I nevertheless quickly checked his immediate surroundings to make sure that the mist that morphed into a cloud did not come from the smoke of gunpowder, his environs or elsewhere. None.

And at that precise moment, I intuitively grasped a powerful message, directed to me, as if an injunction. An invisibility—from or within the slain man—imparted to me a message, an injunction, that right there and then struck me. Faster than the blink of an eye, simultaneously with that message, I saw (albeit not in the physical, but clairvoyant sense), the image of two lines—one horizontal, the other vertical—move to form the shape of a cross; along with instructive energy for me to live so accordingly. Intuitively, I grasped its mystical meaning: Live vertically—communion with the Divine Supreme God—and horizontally—in service to others, for the people. It was a vertical and horizontal relationship. Vertical with the Divine Supreme God, and horizontal, with the rest of my fellow human beings. Subsumed in this mystical moment was the message to me, with a sense of utter certainty, that I will survive, and live through the ongoing bloodbath. The energy of the bloodied man’s utterance—“Diyos ko, ‘wag mo ‘kong pabayaan. Maglilingkod pa ‘ko sa sambayanan!” (My God, don’t forsake me. I will still be serving the people!)—enveloped my whole being with an aura of peace and love. It was soft, quiet, loving, peaceful, assuring, and gentle. It was a split-second moment of mystical experience.

I grasped the injunction and moved quickly again.

Moments later, when only intermittent gunfire from afar can be heard, I turned to the man on the ground. Right away, I knew he was already lifeless. I would, moments later, carry him—the first one—followed by two other fallen marchers with the help of Mat and other photojournalists. His body was still warm, and supple. His head swayed downward on its own weight as we lifted and carried him toward a media service vehicle. The silence I felt deep inside me was quite heavy.

I never came to know the name of the man. My heart nudged me with the imperative of trying to know who he was, his story, his name. Yet, I never had the chance to. (I tried but thought that none of the remains of the marchers whose wake I had attended later in Mount Carmel Church, Quezon City, and in the office of the labor organization Alyansa ng mga Manggagawa sa Malabon (Malabon Labor Alliance) in Malabon, Metro Manila were probably his.) The fourth, farthest man from where we were, had already been quickly carried away, first by two, then by a third photojournalist who ran to help the fallen marcher.

An act of humanity.

What can a person do? Knowingly carrying someone whom you knew from the sight and feel of it to be already dead? Yet still, carrying his body as if he could still be revived and saved? I knew no such miracle will ever happen. I knew they were all dead. But something inside of me cannot resist the act of helping carry their dead bodies to be driven away to hospitals. No, leaving them there was not an option at all. An act of humanity maybe? Compassion? Empathy? Respect for the fallen?

Not a single soldier, not a single law enforcer came to the succor of any of the fallen. Photojournalists—clutching their camera in one hand, or simply strapping it around their neck—without any hesitation, did. Media drivers quickly drove their marked PRESS jeepneys to meet photojournalists carrying the bloodied, slain marchers. And after their unmoving bodies were slumped atop the hood, drivers in quick succession, sped away.

None of the marchers could have survived.

At that moment, I greatly admired and respected the photojournalists who ran towards the slain marchers, lifted, carried, and brought their bodies to media vehicles, and whose drivers sped away to take them to hospitals immediately after the gunfire stopped. At that juncture, it was not over yet because police officers wearing gas masks on board military jeeps chased and fired more teargas canisters toward demonstrators who were no longer visible from where we stood. Several popping sounds can be heard from afar as police fire tear gas canisters. Tear gas, smokeless, continued to bite harshly. Eyes, lungs, skin. All over.

——-

About the Author: An award-winning investigative journalist and licensed attorney, Perfecto Caparas serves as a teaching fellow and founding director of the Center for Holistic International Human Rights Law Praxis of the National University of the Union of Myanmar-Burmese American Community Institute.