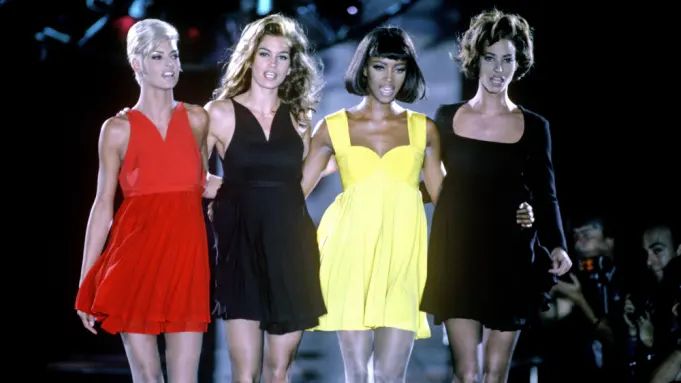

THE four-part docuseries, “The Super Models”, currently streaming on Apple TV+, dives deep into the world of fashion’s most iconic names: Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington. Dominating the catwalk and magazine covers, they were the faces of the ‘80s and ‘90s.

The fab four of Gen X fashion not only star in the series but are also executive producers. Directed by Roger Ross Williams and Larissa Bills, “The Super Models” brings the quartet together for in-depth interviews and archival looks into their illustrious careers. Told in four parts – “The Look,” “The Fame,” “The Power” and “The Legacy” – it also sees the women sharing their struggles, heartaches and triumphs that got them to where they are today while they talk about the positive changes they hope to make for future generations of models.

The new film about the four first ladies of ‘80s and ‘90s modeling shows their industry’s dark side, but its heart is their genuine bond. Here are some takeaways that will make viewers see them as not just supers, but superhuman.

Racism in the industry

“What the white model was getting, I wanted it too,” Campbell said in the series. But she faced more barriers to success than her white counterparts. Before she left England for the US to pursue her career, her mother warned her about racism in America. “I started to understand, culturally, that I was gonna have to work really hard to feel accepted.”

“Naomi, I thought, was more beautiful, had a much more rockin’ body than I did and a better strut, and I’m like, why aren’t they booking her?” Evangelista said. So, she and her friends responded with collective action. “I said to them, if you don’t book her, you don’t get me.”

Campbell confirmed: “Linda and Christy absolutely put themselves on the line. They stood by me, and they supported me. And that’s what kept me going.”

Campbell remembered that after getting booked on runways, ad campaigns then posed their own challenges. Sometimes she wouldn’t be included “and that used to really hurt me.” There were other times she was hired simply to “appease” her. “Then I’d go to the shoot and sit there from nine to six all day and not be used. It made me more determined than ever.”

Sexual assault

While working as a young model, Campbell attended a photoshoot where an art director touched her breasts without her consent. “Once an art director felt the need to tell me my breasts were perfect. But he felt the need to have to touch them,” she said.

Campbell confided in her mentor, the late fashion designer Azzedine Alaïa, after she was assaulted. Alaïa, whom Campbell endearingly refers to as “Papa” throughout the documentary, “protected” her when she was breaking into the fashion industry. “I called Papa immediately,” she said. “Papa called (the art director) up straight away. Never came near me again. It served that I opened my mouth and spoke my truth because I believe that protected me, as well as everyone that I was surrounded by.”

On being labeled as ‘difficult’

“It was hard to be an outspoken black woman, and I definitely got the cane for it many times,” Campbell said. One of those instances was when she was working with the late modeling agent John Casablancas on a potential deal with Revlon, which she turned down once she learned she’d be making significantly less than her counterparts. When she left Casablancas’ agency, he then went to the media, portraying her as difficult.

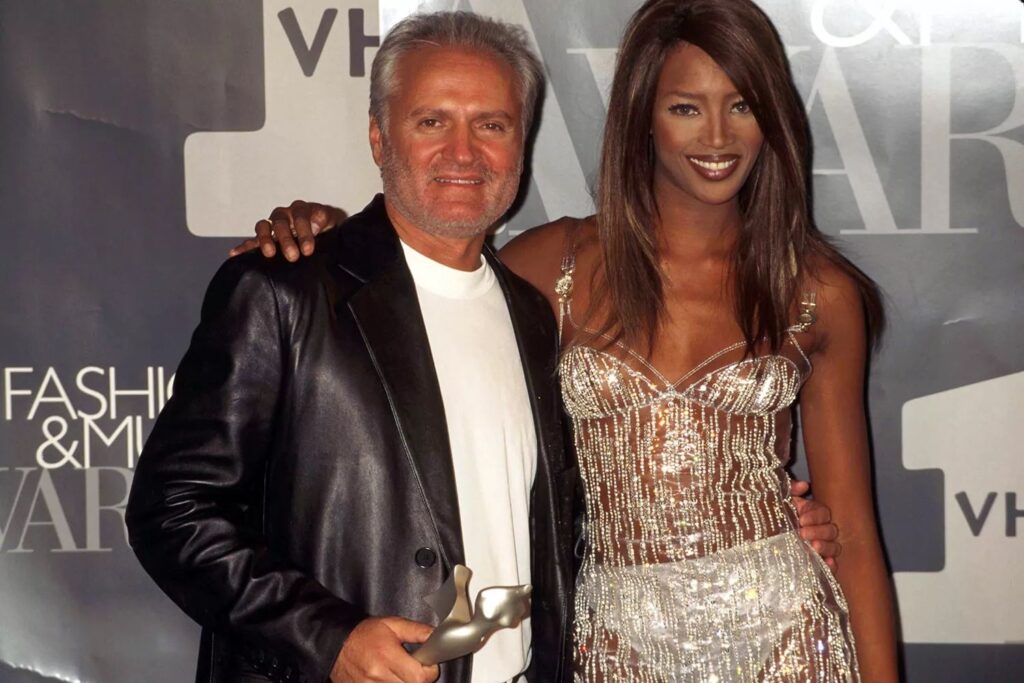

Campbell also reflected on how the assassination of Italian designer Gianni Versace, a close friend, in 1997 led her to turn to drugs to “cover up” the pain. “My mistakes, I’ve always owned up to them,” she said. She chose to go to rehab, which was “one of the best and only things I could’ve done for myself at that time.”

She also paid it forward. Designer friends Marc Jacobs and John Galliano attested in the docuseries to Campbell’s support when they were struggling with partying or drug abuse, respectively.

Treated ‘like chattel’

On her 1986 appearance on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” Crawford said Winfrey’s treatment of her was “not okay.” In an old clip shown in the docu, Winfrey is heard asking Crawford, “Did she always have this body? This is unbelievable. Stand up just a moment, now this is what I call a body.”

In retrospect, Crawford realized, “I was like the chattel or a child, be seen and not heard. When you look at it through today’s eyes, Oprah’s like, ‘Stand up and show me your body. Show us why you’re worthy of being here.’ In the moment I didn’t recognize it and watching it back I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, that was so not okay really.’ Especially from Oprah.”

Father thought modeling was another form of prostitution

“My dad really didn’t understand that modeling was a real career. He thought modeling was like another name for prostitution,” Crawford said. “So (my parents) came with me to my very first modeling appointment. I never even thought about modeling. I didn’t even know it was a real job.” Even once her career began to take off, Crawford was still more interested in pursuing academics and going to college than landing the cover of a magazine.

Posing for Playboy

While everyone in her life thought shooting for Playboy would be the death knell of her career, Crawford saw it as an opportunity to take ownership over her own image, calling the entire experience “empowering.” While it “was definitely outside the normal trajectory for a Vogue model at the time,” there was “something about it that intrigued” her.

Crawford shot the editorial with the late fashion photographer Herb Ritts in Hawaii. Her one stipulation was that they didn’t need to pay her a lot to do it. “As long as I have control of the images and I wanted the right to kill the story if I don’t like it,” she said. “I never felt like a victim of that decision.”

Lifelong aversion to short hair

Crawford got her first big break when she booked a shoot in Rome with the late fashion photographer Patrick Demarchelier. However, the lensman wanted her to cut her hair very short before they worked together, but both she and her agency decided it wasn’t worth it and told Demarchelier she wouldn’t do it. He agreed to take her on the shoot anyway.

Once she arrived in Rome, it was a different story. “The very first night, they sent the hairdresser to my room to give me a ‘trim.’ They combed my hair, put it in a ponytail, and chopped my ponytail off without asking. I was in shock and I just sat there in a hotel in Rome crying. And people wonder why I’ve never really cut my hair since then – that’s why. I was so traumatized.”

Molding herself around Richard Gere

“I think I was 22 when we met. In the beginning of a relationship, when you’re a young woman, you’re like, ‘You like baseball? I like baseball. Oh, you’re really into Tibetan Buddhism? I might be into that. I’ll try that.’ You’re willing to kind of mold yourself around whoever you are in love with.”

Crawford was 25 when she married the then 42-year-old Gere in 1991. They were together for four years before they parted ways in 1995. She added that her relationship with the actor took place during a “time in my career when I veered away from the high fashion elite and took more control.” In 1992, Crawford starred in the Pepsi Super Bowl commercial which catapulted her into stardom.

Crawford also looked back on the couple’s 1991 Oscars appearance. She wore a red Versace gown with a low neck and high leg slit. “I got invited to go to the Oscars with Richard. I’m like, ‘Well, what do models do well? We wear clothes well.’ I mean, I better look good. That was kind of what my thinking was, like, ‘I’m gonna go to the Oscars, I better be a freakin’ supermodel.’”

The infamous ‘less than $10K a day’ quote

Evangelista’s quote – “I will not get out of bed for less than $10,000 a day” – became one of the most notorious statements in modeling history after it was published in an interview with Vogue in 1990. Today, Evangelista said she doesn’t “want to be known” for that.“I’m not the same person I was 30 years ago. I shouldn’t have said that. That quote makes me crazy. I don’t even know how to address it any more.”

Evangelista also claimed the situation would have been different if a man had said it instead: “If a man said it, it’s acceptable. To be proud of what you command.”

Abusive relationship

Evangelista and Gerald Marie, the head of Elite Model Management, wed in 1987 when she was just 22 years old. The couple were together for six years before they divorced in 1993. “It’s easier said than done to leave an abusive relationship. I understand that concept, because I lived it. If it was just a matter of saying, ‘I want a divorce, see ya’… it doesn’t work that way.” She added that Marie “knew not to touch my face, not to touch the money maker.”

Marie was accused of rape and sexual assault by several women during the 1980s and 1990s. He denied the allegations and eventually prosecutors closed the investigation earlier this year due to the statute of limitations.

“I would love for justice to be served. I would love for assholes like that to think twice and be afraid. I would love women to know they are not alone,” Evangelista said.

CoolSculpting nightmare

Evangelista said she sought out the cosmetic treatment CoolSculpting, which removes fat by freezing it in a non-invasive manner, to help maintain her looks. The procedure, however, left her with a rare complication called paradoxical adipose hyperplasia or overgrowth of fatty tissue.

“The commercials said I would like myself better. But what happened to my body after CoolSculpting became my nightmare,” Evangelista said. “I can’t like myself with these hard masses and protrusions sticking out of my body. That is what has thrown me into this deep depression that I’m in. I never went out the door unless it was maybe a doctor’s appointment that I had to go to.”

Evangelista also opened up about being diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoing a double mastectomy, only to be diagnosed with cancer a second time. “I can celebrate a scar – but to be disfigured is not a trophy. I can’t see how anyone would want to dress me. Now, to lose my job that I love so much and lose my livelihood. My heart is broken.”

Posing topless at 17

Turlington recalled taking nude photos for Demarchelier during a cover shoot for British Vogue: “After we finished the shoot, we took a portrait where I was, like, covering (her hands over her breasts). The classic covering yourself.”

Demarchelier then asked her, “Can you put your arms down a little bit lower, a little bit lower.”

“I remember being self-conscious, but I didn’t feel necessarily bad. I felt good from that shoot, I felt pretty in that moment,” Turlington added. “Patrick didn’t give me the creeps, per se, but I do remember being like, ‘Oh my gosh, I shouldn’t be doing this.’”

Much to Turlington’s shock, the photo was published on the cover of Photo magazine. “It was still like, ‘Oh gosh.’ I don’t know what I thought it was for, but I definitely didn’t think it was for the cover of a magazine. I don’t think there was any age that you were supposed to be in order to have a nude picture. I don’t think there was anyone monitoring or regulating any of that.”

In 2018, Demarchelier was accused of sexual harassment by seven models who worked with him. Vogue publisher Condé Nast subsequently announced that they would “not be working with (Demarchelier) for the foreseeable future.”

Encounter with Epstein associate

“I met Jean-Luc Brunel, who was the infamous French agent who was running Karin’s (modeling) agency in Paris at that time,” Turlington said. “And they were like partners, Ford’s and Karin’s. I would go to Paris, and the Fords would have it set up so that I would stay at Jean-Luc’s apartment.”

Brunel was accused of rape, grooming and partaking in the alleged sex trafficking ring run by convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. In 2022, Brunel committed suicide prior to the start of his trial.

“Nothing happened, most of the time he wasn’t even really there. I got angry just looking back, and thinking like survival skills, like guilt, I can’t believe I’m okay,” Turlington continued. “Nothing really surprises me about anybody. I feel like even people you know you just don’t know what they’re capable of.”

Hemorrhaging after childbirth

Turlington explained where her interest in women’s health, specifically reproductive health, and her charity Every Mother Counts originated. When she got pregnant with her first child, Grace (who’s now 19), she and her husband (actor and filmmaker Edward Burns) were “super excited” and she was “so ready for this next adventure and phase of my life. After I delivered, I hemorrhaged. It became a complication that had to be managed, which was painful and I lost a lot of blood, but my child was born, she was healthy.”

The experience, though, made her want to do something to help other women in similar situations. “I was so informed and I had so many resources, why did I not know this was possible and why did I not know that so many women die from similar complications around the world? I just sort of dove in and started this organization called Every Mother Counts.”

Putting young designers on the map

Campbell, Crawford, Turlington and Evangelista’s presence at runway shows would garner so much press attention that designers were dying to cast them to create buzz around their brands. (After falling at a Vivienne Westwood show, Campbell even remembered designers asking her to fall on their catwalks just to generate press.) But some of the newer designers couldn’t afford to put a supermodel in their roster, including Marc Jacobs in his early years.

He would ask agencies if any models would work for free clothes, and Turlington did. “And then the next season when we did a show, Christy asked Cindy, then there was Naomi, then there was Linda,” Jacobs said in the docuseries. “The attention just kind of grew and grew and grew and grew, but it was all because of Christy.”

Anna Sui and Isaac Mizrahi had similar stories.

Impact of gay culture

The ballroom scene and queer community were inspired by the high fashion world, but the influence went both ways, the models say. “I really believe gay culture and the drag community helped me flourish,” Evangelista said. “Because they’re larger than life. They’re like what I want to be, but bigger and better. And with confidence.”

She gave props to American drag queen RuPaul and said getting name-dropped in his song “Supermodel (You Better Work)” is a “major honor.”

After all, their collaboration with the late George Michael, a trailblazing gay pop star and LGBTQ+ advocate, marked a major change in their career. He invited them to appear in his “Freedom! ’90” music video, which launched them not only into fashion acclaim but also pop culture stardom.

Beauty standards and aging

The foursome, who are all in their 50s today, opened up about aging in the modeling industry, which they started working in as teenagers. “So many barriers have been taken down since I started modeling,” Evangelista said. “Age was one of them. They used to say beauty’s not sustainable. Youth is not sustainable; beauty is. There’s a difference.”

In one behind-the-scenes clip, Campbell laughs off having hot flashes mid-photoshoot. She said at times she’s thought about slowing down or pulling back on her modeling career, but her “energy is still the same.”

Crawford also briefly acknowledged that the beauty standards she and her peers embodied, especially at the height of their careers, weren’t very accessible or inclusive. They were “the physical representations of power,” she said. “And where it gets tricky and hard to talk about is that some people don’t fit that, and then they’re made to feel less beautiful.”

As social media continues to democratize fashion and help uplift more diverse beauty standards, Crawford wondered, “Maybe the idea of what a model is and represents now has picked up steam, and maybe that’s a great thing. There’s all these different ideas of beauty now. And all of a sudden that is creating its own stars, its own momentum, its own energy and its own ideas.”

Fulfillment beyond modeling

Decades into their careers, Campbell, Crawford, Evangelista and Turlington have achieved so much beyond the runways, through motherhood, philanthropy and their own businesses.

“Becoming a mom, that’s the most fulfilling thing that’s happened to me,” Evangelista said of her 16-year-old son, Augustin James.

For Turlington, fronting anti-smoking campaigns and supporting maternal health; for Campbell, supporting burgeoning designers, especially those from Africa; and for Crawford, her business endeavors – from skincare to furniture – and mentoring her two model children, Presley Walker, 24, and Kaia Jordan Gerber, 22. (Crawford is married to businessman and former model Rande Gerber since 1998.)

Turlington said that their longevity is “the opposite” of what she imagined her career would be like in the industry when she first started.