DIRECTED in borderline worshipful fashion by Thom Zimny, executive produced by Sylvester Stallone and running for a short one hour and 35 minutes, the Netflix documentary “Sly” (which closed this year’s Toronto International Film Festival) is at its most fascinating when the 77-year-old Stallone regales viewers with tales of his hardscrabble childhood in Hell’s Kitchen in New York City, his early struggles as an actor and aspiring writer, and of course, the oft-told but still incredible behind-the-scenes story of the making of “Rocky,” and how a broke, out-of-work, unknown Stallone turned down hundreds of thousands for the screenplay, insisting he play the title role himself.

For those who fell in love with “Rocky” and have stuck with him, it’s pure docu gold when “Sly” recalls how the film was shaped, e.g., the budget couldn’t accommodate 300 extras for the ice skating sequence, so Stallone rewrote it that the rink was closed and Rocky had only enough money for a quick 10 minutes’ time with Talia Shire’s Adrian – which made for an instant classic of a scene.

For Zimny, this is relatively new territory. He has worked on shows like “The Wire” and “Independent Lens” as an editor, but as a director, he’s best known for his work on music-related films, including “Willie Nelson & Family,” “Elvis Presley: The Searcher,” “The Gift: The Journey of Johnny Cash” and almost 30 documentaries, music videos and concert films with Bruce Springsteen. Stallone, though, is not about the music – as the few who’ve seen his lamentable team up with Dolly Parton in the 1984 flop “Rhinestone” can attest.

“It was chasing an understanding of who he was in the world and all the things that he went through,” says Zimny. “I’ve loved all (Stallone’s) films since childhood, but I started to realize in the making of this that I was getting a side of a man that just had not been seen before.”

“Sly” builds a framework around Stallone selling his enormous mansion in Beverly Park filled with old scripts, action figures, busts and paintings of Rocky and Rambo and other Stallone paraphernalia.

“I can feel myself withering, drying up,” says Stallone, explaining that he’s leaving his Los Angeles house in search of new adventures out east.

Judging by the numerous shots of Stallone gazing pensively through the floor-to-ceiling windows or leaning against a palm tree, smoking a cigar, while movers carefully wrap pieces of art and carry out a huge Rocky statue, you’d think the actor was living out his days in some sort of self-imposed isolation, but as we know from “The Family Stallone” reality show and social media posts and countless stories, Stallone has been married for 25 years to Jennifer Flavin with whom he has three daughters – Scarlet Rose, Sistine and Sophia Rose.

(Stallone also had two sons, including Seargeoh, who has lived out of the spotlight, and Sage, who played his son in “Rocky V” and who died of coronary artery disease in 2012 at age 36. In the most personal segment of the documentary, Stallone speaks with candor about how Rocky’s relationship with his son in “Rocky V” mirrored his own failures as a father with Sage.)

While removal men pack up his home, Stallone unpacks the story of his life in that trademark drawl. The “snarl”, as he calls it, was a result of complications during childbirth and a concern for casting directors early in his career. But it’s the emotional scars of a childhood shaped by negligence and abuse that still trouble him. The approval and attention he gets from audiences, he suggests, has always been a substitute for the love denied by his parents. Such moments of self-analysis might come as a surprise from a man more associated with muscularity than sensitivity.

Shire, Quentin Tarantino, Frank Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger offer some insightful bits of commentary in the largely first-person retrospective. Stallone talks about how Rambo was initially a psychopath but was shaped into an anti-hero and acknowledges that his forays into comedy (“Oscar” and “Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot”, the latter of which Stallone took on, according to Schwarzenegger, because of their intense rivalry) were disastrous.

But there’s no mention of the multiple (denied and uncharged) accusations of sexual assault and abuse (including by his half-sister) Stallone has faced, the soft-core porno “The Party at Kitty and Stud’s” he made in 1970, the “Creed” franchise, his triumphant work in the Paramount + series “Tulsa King” and the mega-mansion he is leaving was sold to English singer-songwriter Adele for $58 million.

Rather than a recap of all the work he’s done in 50 years, the documentary feels like Stallone taking inventory of his own life as it evolved through the movies. He talks about how “Rambo” is more than gunfire and explosions or why “Rocky” is more of a gritty melodrama. There is genuine thought about how he was approaching his art and what it was that he wanted to do with each new film he made. More than anything, it proves that Stallone remains an underrated screenwriter who is more than just an action star. It is about understanding what made him tick rather than just the end result.

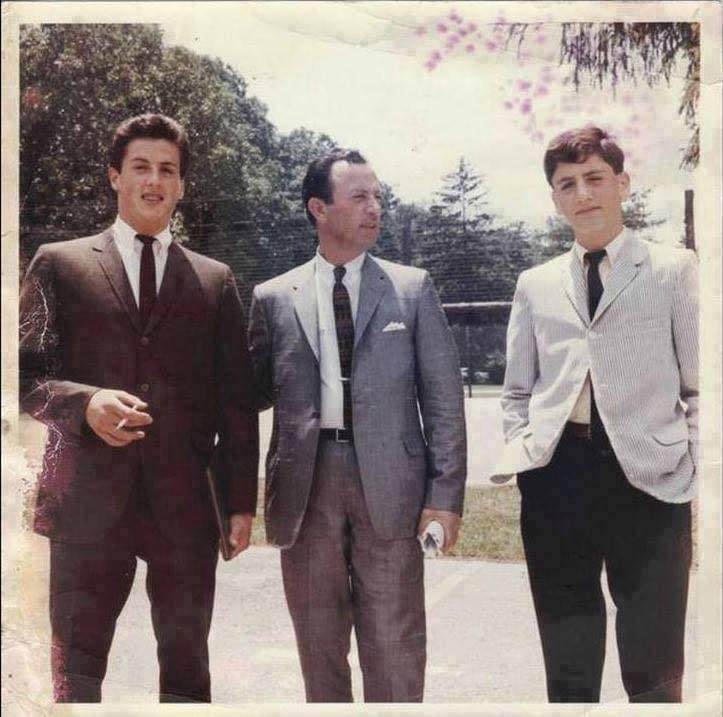

Childhood was not too kind

Life wasn’t easy for Stallone and his younger brother Frank. The blame for that goes to no one but their domineering mom and physically brutal dad, who didn’t have an easy marriage. And not only did they fail to protect the kids from the trauma of that, but they also made Stallone and Frank a part of it. When their parents finally separated, Stallone ended up with his father in Maryland, and, by his account, suffered repeated physical and emotional abuse; Frank settled with their mother in Philadelphia. That was difficult for the brothers, as told by both in the documentary, who always shared a strong bond between them. In Maryland, Stallone discovered his love for horses and polo, but his abusive father played a spoilsport in that as well. It was only a matter of time before he broke out of his father’s house and ended up in New York with the dream of becoming an actor.

The acting dream mainly happened due to the 1958 film adaptation of “Hercules” where the leading man’s flawless physique inspired Stallone to find the way. He immediately knew the kind of thing he wanted to become on screen. Not that it happened overnight. The acting career of the future superstar actually had a modest start with the play “Death of a Salesman”, where he got noticed by people. But Hollywood wouldn’t cast him in lead roles as Stallone looked much different from the leading men of that era. Realizing he had to find his own way, Stallone took the mantle of writing screenplays on his own while working at a movie theater. A meeting and subsequent friendship with actor, director and screenwriter John Herzfeld, who was also trying to make it big at the same time, set the course of Stallone’s upcoming future. The first taste of success came for him with the 1974 drama, “The Lords of Flatbush”, which also formed another of his longtime friendships with actor Henry Winkler, who couldn’t be more different from Stallone.

‘Rocky’ and instant stardom

Stallone’s career did take off with “The Lords of Flatbush”, but it was “Rocky” that changed the course of his life. The 1976 boxing film, which gave birth to a super-successful franchise is still going strong. It was the kind of thing an actor could only dream of. Possibly the greatest underdog story ever told, where the underdog actually lost in the end but still managed to win the hearts of millions, “Rocky” turned Stallone’s life upside down and dropped him into the world of glitz and glamour. Everyone now wanted a piece of this new guy. Some of them couldn’t believe he was the same guy from “The Lords of Flatbush” as told by none other than Tarantino.

Slew of failures

With great power comes great responsibility. The pressure of delivering a worthy follow-up to “Rocky” was always a difficult job. But Stallone completely messed it up with “F.I.S.T.”, the neo-noir crime film where he played something completely different from Rocky Balboa. Things got further worse with his directorial debut “Paradise Alley”, another boxing film, but of a very different kind compared to “Rocky”. With his career at stake, Stallone did what anyone would in such situations – going back to the character that gave him everything. That worked out for him, as the second “Rocky” film (this time directed by Stallone himself) was warmly received by the audience as well. Stallone was back in the business again. Four years later, he came up with the third “Rocky” film, which also yielded gold at the box office.

But Stallone needed another character to prove he was worthy of everything. That’s how “Rambo” came along. Rewriting the course of the military action film genre, “First Blood” (1982) proved to be a huge success, and after that, Stallone never really had to look back.

At the time, Stallone’s mother, astrologer and promoter Jackie Stallone was often in the news. But in “Sly,” Jackie is far less of a presence than her husband, Frank Stallone Sr., a barber. “I know I got a certain kind of ferocity from my father,” says Stallone. He goes on to describe the original Rambo character as a homicidal maniac and then says, “My father was Rambo in reality.”

‘The Expendables’

Stallone is probably the only person to create not one or two but three successful franchises. The final one came with “The Expendables”, the 2010 action film where he managed to bring in other action superstars like Jason Statham and Jet Li. Subsequently, Mel Gibson and Harrison Ford also joined the franchise in later movies. Although not particularly well received by critics, “The Expendables” franchise remained a huge financial success and is still going strong, given that the fourth one was released only a few months ago.

Key to life and career

Stallone makes clear that his old man’s violence and lack of support drove him to court audiences’ acceptance and adoration, as well as to make that a constant theme in his work. Nowhere was that more evident than in “Rocky”, the Oscar-winning saga that turned the struggling actor-writer into an overnight sensation and forever changed his personal and professional fortunes.

Zimny’s film spends considerable time on “Rocky” and, in particular, the many ways in which it reflected Stallone’s own situation at the time – a life-imitating-art dynamic that would continue throughout the majority of its sequels. In those parallels, as well as the connections between Stallone and his other famous role, Vietnam War veteran John Rambo, “Sly” posits Stallone as someone who used genre to express his own fears, dreams and personality. Aided by interviews with critic Wesley Morris, directors Tarantino and Herzfeld, and colleagues and friends Winkler and Shire, it reinforces the image of Stallone as a creative type who projected himself through acting and writing, and how that process resulted in immense critical and box-office triumphs as well as, ultimately, quite a few missteps.

While Stallone’s fraught relationship with his father Frank Sr. emerges as the key to perhaps his entire life and career, most of his other relationships are only lightly referred to. His current wife Flavin appears in the documentary, as do their three daughters, though they don’t speak (Fans eager to know more about the ladies in Stallone’s life can check out their recent reality series, “The Family Stallone,” to learn more.). His first two wives (including “Rocky IV” baddie Brigitte Nielsen) are not mentioned, nor is his second son, Seargeoh. And while the tragic life of his son Sage becomes central to the docu’s second half, viewers who don’t know what happened to Sage might miss some of the resonance of his story.

Surely, Stallone had things he didn’t want to share within the context of “Sly”, and while that leads to a certain unfinished quality to the film, it also makes the things he does share feel more resonant. One gets the sense that any ruminations on the pains and pleasures of fame wouldn’t faze Stallone in the slightest, mostly because he’s clearly spent decades running them over in his own head. And when Stallone offers up his current take on his career – be a specialist within the things you’re best at. So much of the docu hinges on Stallone’s journey to stardom, a truly self-made star who started acting because he loved it, who started writing because he needed it, and who is still very genuinely grappling with his legacy, and there seems to be no end to his creativity. As Stallone says in “Sly”, “Don’t sit there and try to do Shakespeare when you look like me.” Mostly, it’s Stallone who impresses here, as a disarmingly open and self-aware icon whose hardest lessons have left a mark on him.

Nothing earth-shattering

“Hell yeah, I have regrets. But that also is what motivates me to overcome the regrets,” says Stallone at the start of “Sly”. As the ensuing snapshot of the artist conveys, the mistakes that most plague him have to do with prioritizing work over family. Despite much talk about putting his career ahead of his wife and children, though, there’s so little substantial mention of his clan or personal life that the sentiment rings hollow. It’s not that Stallone seems to be lying so much as he wants to grapple with such issues via generalities. By refusing to even say his kids’ or wife’s names on-camera, much less discuss the nature of his relationships with them, he neuters his own purported desire to reckon with the missteps he believes he’s made along his A-list career path.

Stallone expresses the importance of family in his life. “Sly” evidently ends on the same note, as the man keeps talking about family values and the importance of having people to whom you get to come back home. That is admirable, but the issue here is that viewers don’t really get to feel anything for him or his family. A good documentary is supposed to make the audience part of its story by drawing them inside it. And there isn’t anything that seems groundbreaking either. Don’t get me wrong, I have my utmost respect for Stallone, who managed to overcome a harsh childhood. That is indeed an inspirational story, and a lot of his life struggles can actually be seen in the kind of films he has made.

But we are talking about the Zimny-directed docu, which is supposed to depict the life story of the man and make us feel for him. That’s where it falls short. The presence of Tarantino does bring some zing to the whole thing nonetheless.

Altogether, it’s a polished formal package, but its glossiness indicates its disinterest in plumbing the pricklier aspects of Stallone’s saga. The sole time things get thorny are when it tackles Stallone’s dad’s cruelty and compulsion to compete with his son by writing a boxing script called “Sonny” that sought to outshine “Rocky”. Or when Stallone invited his pops to a charity polo match he’d organized in the ‘80s. Unprovoked, and inexplicably, his father whacked Stallone in the back with a mallet, knocking him off his horse. The actor says after that, he sold his ranch, horses, trucks and polo gear and vowed to never play again.

There’s little conversation, and merely the briefest of glimpses, of the actor’s other ’80s and ’90s action hits (“Cobra”, “Over the Top” and “Cliffhanger”); more time is spent on his “serious acting” comeback, 1997’s “Cop Land”, although that chapter goes nowhere, just as the film did with critics and audiences. Primary attention naturally falls on the “Rocky” franchise, yet without any real scrutiny of its highs and lows.

Consequently, Stallone’s candidness comes off as something of a performance itself, crafted to reveal just enough pain and remorse to seem genuine. It skirts in-depth consideration of what made him such a uniquely charismatic star, and how his own ambitions – to play the hero; to cater to viewers’ hunger for uplifting endings; to be a larger-than-life he-man – were both strengths and weaknesses. Rather than an incisive examination of Stallone’s one-of-a-kind appeal and fame, it resonates mostly as a handsome magazine feature disguised as a probing bio-docu.