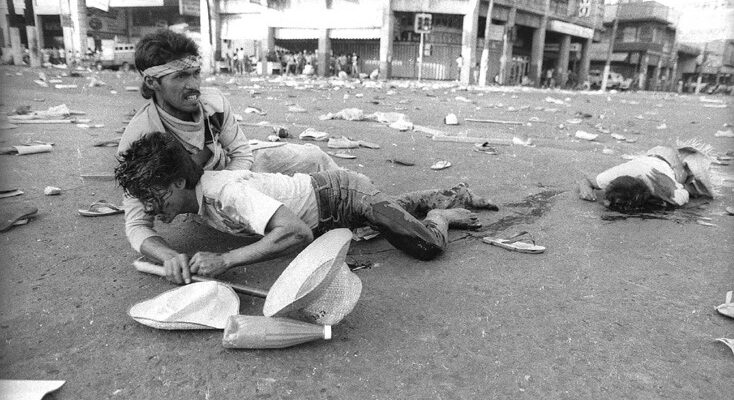

THAT evening after the massacre, Mat and I boarded a passenger jeepney and went to the office of a newspaper that published Mat’s photo on its front page the following morning. His photo captured one of the rarest scenes of the event, a fallen demonstrator. Mat and I did not talk about the specifics of what we had witnessed. He showed me photos of some other scenes he was able to capture—of a raised fist by a young man shouting in defiance, hunkering down in front of a wounded, dying comrade—whom he can no longer carry or bring along with him due to the hail of bullets. Another of several slain demonstrators lying at the foot of Mendiola Bridge. But we just looked at those photos. Silent.

A couple of times too, he talked about the whizzing of bullets around us, our head and body, saying bullets were “ricocheting” everywhere. I remained quiet. The third time he mentioned it, I looked him in the eye and told him, “Pinaputukan tayo.” (“We were fired upon.”)

Mat was stunned, mum.

The scenes of the massacre have never really left me, although I had tucked those away somewhere where I cannot reach or delve into them; but I knew those have always been a part of me, deep, deep within me. Those have been etched at the core of my being. The staccato of gunfire, the scenes of demonstrators swiftly falling as if swept by blasts of wind, amid the smoke of gunpowder. The biting, toxic, excruciating sensation of tear gas to the eyes, throat, lips, mouth, lungs, and skin…. The scenes ran for seconds. The stark imagery of the fallen marchers… One by one, while watching them fall from where I was initially crouched, half-kneeling; crossroads of disbelief and a stab of reality pierced my mind. In intervals of nanoseconds, one by one they fell. I deliberately kept my mind and vision alert then, knowing that what I was witnessing was a historic event; while enveloped by uncertainty as to whether Mat and I will survive. I mentally counted eight demonstrators—one by one—falling as bullets hit them. Falling as visibly freshly slain bodies surrounded them.

Aftermath

Earlier, as I watched them defiantly face the hail of bullets, I knew they got no chance of surviving. Their death in all certitude was instantaneous. The bodies I helped carry minutes earlier in front of the Corona Book Supply were all lifeless. Their gunshot wounds were all to the head. The brains and blood of one of them—the last one I lifted up and carried—even slithered down my arm, hand, bag, pants, and shoe. Looking at my arm and hand immediately afterward, I felt stumped, wondering what it was. When the realization dawned on me, I screamed in shock: “Utak! Utak!” (Brains!) I retched.

I scoured the foot of Mendiola Bridge afterward. Rubber shoes, backpack, shirt, broken placard, streamer, handkerchief, bandana, rocks, wooden stick—abandoned by those who hurriedly left the pandemonium. No weapon. No gun. No grenade. I did not see a single metal bar from the fence earlier ripped apart by of demonstrators at Liwasang Bonifacio.

Pools of blood showing signs of beginning to dry up.

After helping photojournalists carry the fallen, I approached the centerline at the foot of Mendiola Bridge where the eight frontliners died. The smoke from gunpowder had relatively cleared. Three of them lay lifeless atop each other. Their bodies were randomly heaped atop each other. They were young. Perhaps in their early 20s. A uniformed police officer looked happy.

Scores were wounded. Days later, I met and interviewed one of them—a young worker who was manning their picket line at a factory in Valenzuela, Metro Manila prior to the march. He was confined at the Philippine General Hospital, located along Taft Avenue, Manila. His first question upon seeing me, and that was for the first time, was: “Where is my eye?” Innocently he asked. He lost an eye due to gunfire at Mendiola. The bullet pierced through his eye and exited near his temple. I thought it was a miracle that he had survived.

Noncombatants

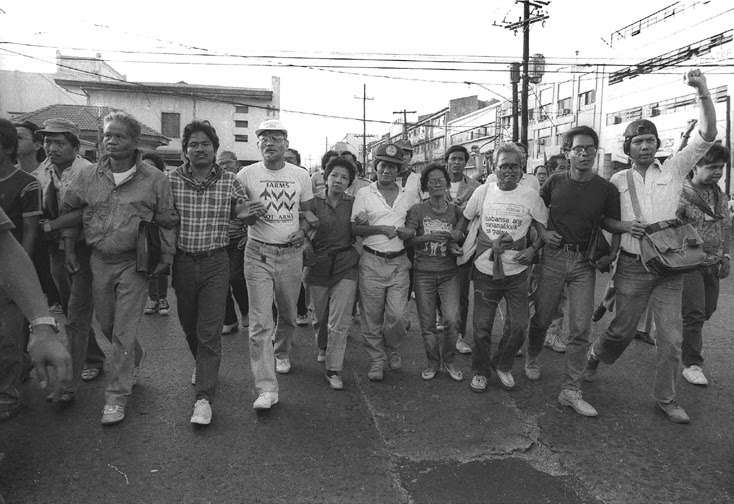

This is more than a survivor’s personal and journalistic narrative. It is a historic moment in Philippine history. It is known as the Mendiola Massacre. At least 13 marchers were killed. It occurred less than a year after the February 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution that ousted fascist Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

In hindsight, as I reflect, the eight demonstrators—whom I had seen with my own eyes felled one by one by rains of bullets—occupied the front and center of the demonstrators’ line at the foot of Mendiola Bridge. Before being slain, sporadic bursts of gunfire had already erupted and begun to intensify several minutes earlier. The intersection of Mendiola, Claro M. Recto and Legarda streets had already been cleared of thousands of demonstrators (who, with lightning speed, frenziedly scampered away, driven out and chased by hails of bullets) when those eight demonstrators were mowed down.

Years later, as I revisited this macabre scene in my mind, I came to realize that those eight demonstrators, like me, could just as easily have opted to drop to the ground as soon as the shootings started in order to try and avoid getting hit somehow. Now, I realize that their being sprayed with bullets while standing on their feet and while deliberately facing armed Marines soldiers and police officers was their own conscious choice. They refused to turn their back and run away just like what the thousands of demonstrators instinctively did. Opting to stay, they neither dropped to the ground to avoid getting hit.

Standing on their feet to face bursts of gunfire speaks volumes. They did not blink nor balk. Only one (he was wearing a white shirt) stooped involuntarily while falling, not because of fear, but because of the bullets that apparently peppered his body’s mid-region. The rest were swiftly swept down by gunfire while standing straight, all while facing their shooters. They made a brave, last stand.

Defiance.

Their refusal to drop to the ground or to run, their decision to stay on, to hold the line, to keep standing facing bursts of gunfire was political. It was a message.

Conviction.

They stood for and defied death for their conviction.

Theirs, now I realize, was a warrior’s stand.

Unarmed resistance.

Time passed. On occasions, upon waking up, my consciousness asked:

“Why am I still alive?”

Coming from my innermost recesses. I did not know the answer. Something… something moves me on. There must be a reason.

One morning, the answer came in:

Mendiola.

I live for those who passed on, for those who now live, and for those who—in the future—will live.

We are one.

—

About the Author: An award-winning investigative journalist and licensed attorney, Perfecto Caparas serves as a teaching fellow and founding director of the Center for Holistic International Human Rights Law Praxis of the National University of the Union of Myanmar-Burmese American Community Institute.